The NANOGrav 12.5-year Data Set: The Frequency Dependence of Pulse Jitter in Precision Millisecond Pulsars

by the NANOGrav Collaboration; corresponding author: Michael T. Lam.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal, February 25th, 2019.

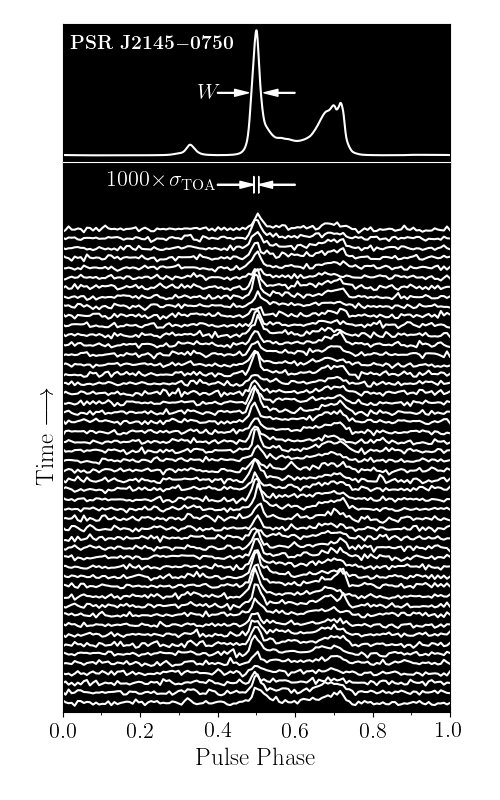

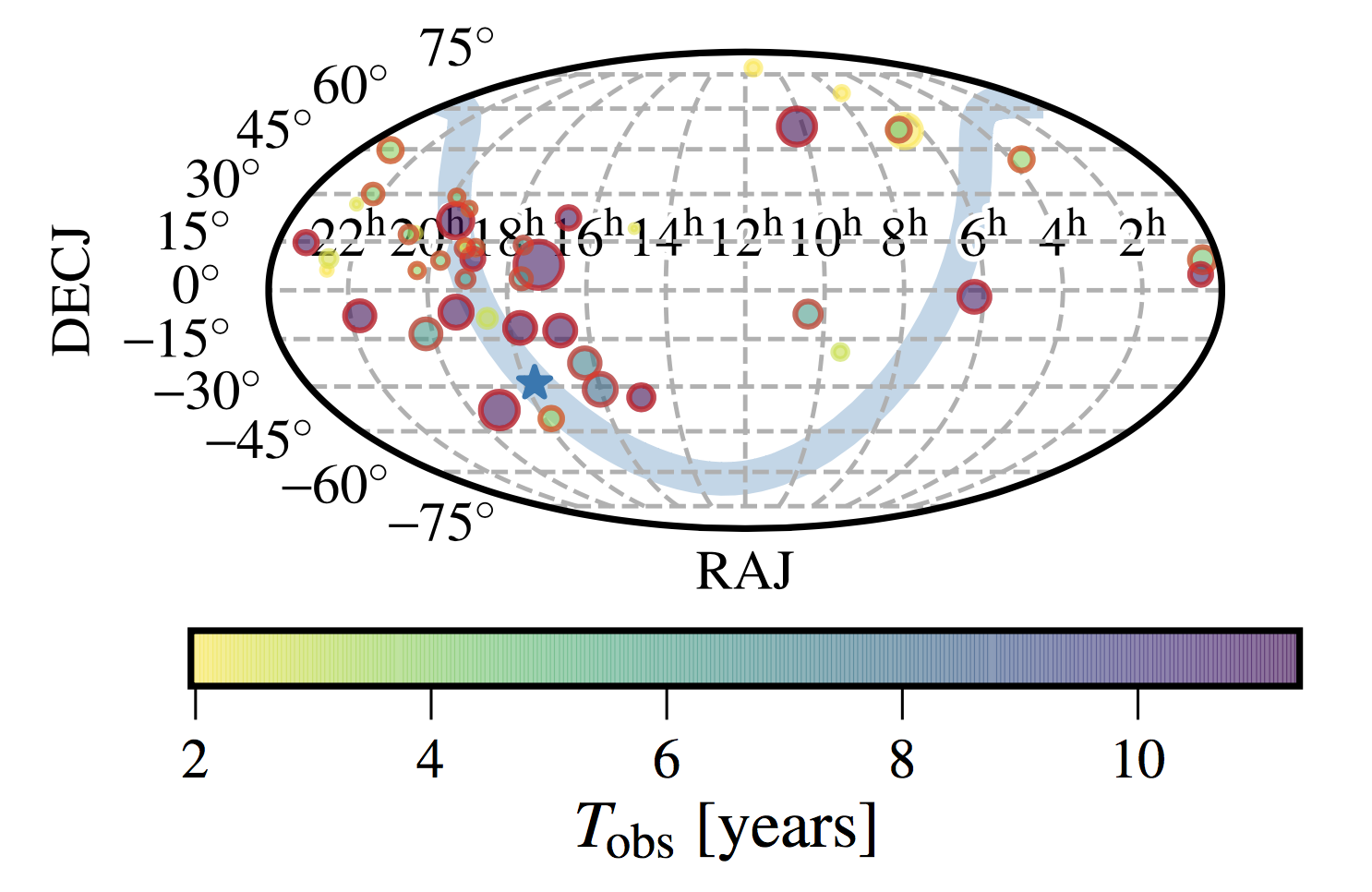

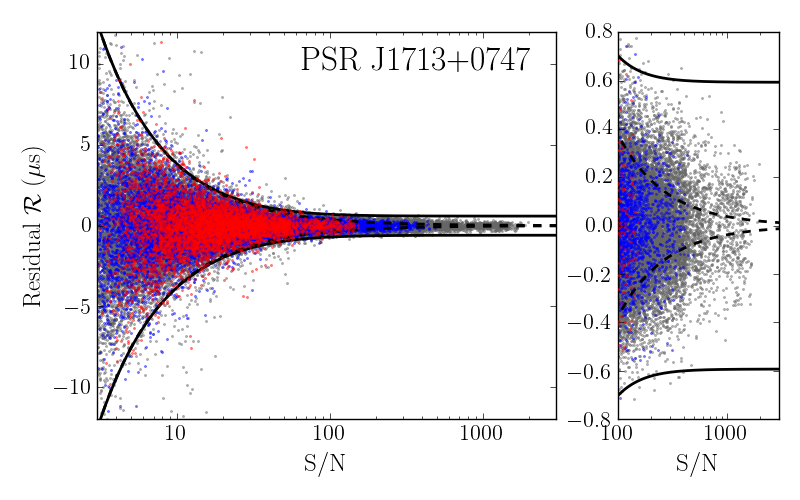

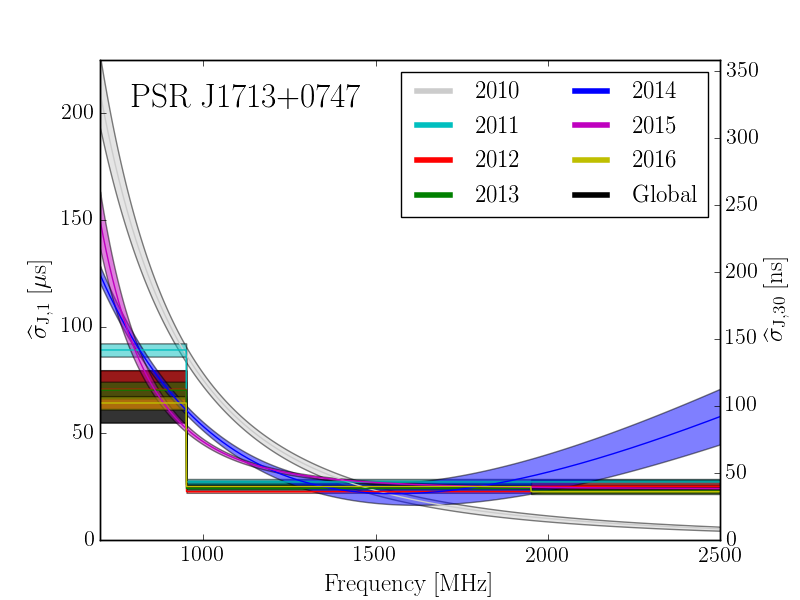

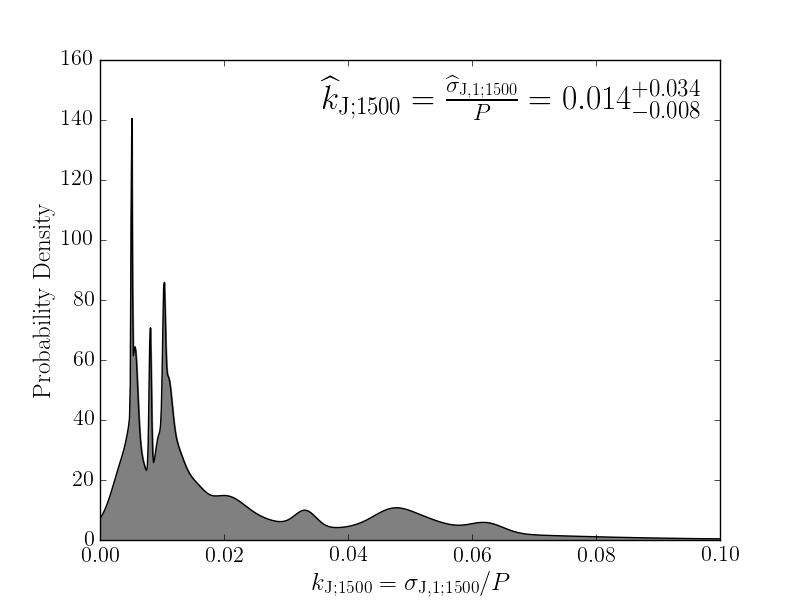

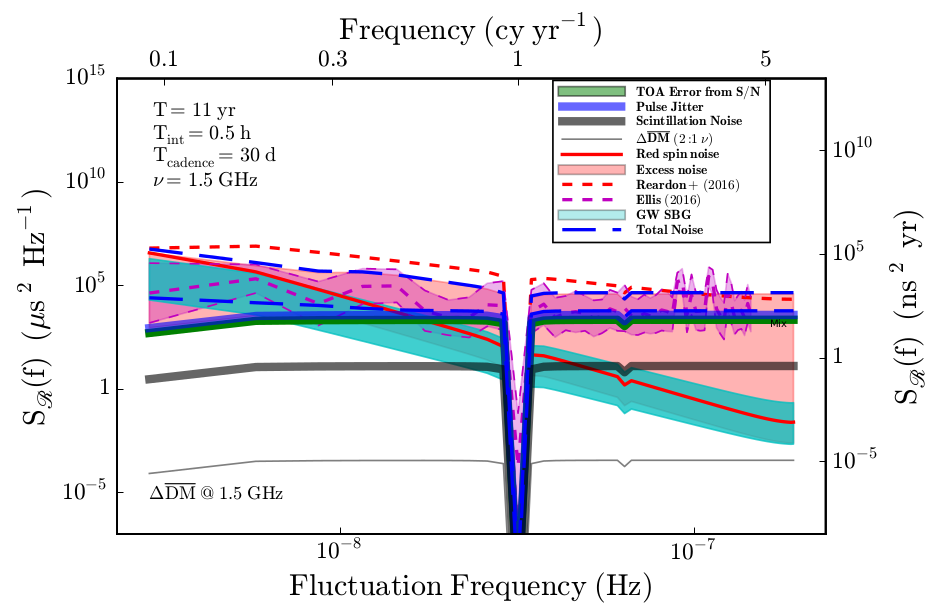

We analyzed the NANOGrav 12.5-year data set from the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) for pulse jitter, the effect that individual pulses look different from the very stable average pulse shape. The result is an increased uncertainty on our times of arrival and therefore pulsar timing experiments must properly model jitter as a significant component of noise within our Galactic-scale detector. While the dependence of this effect with radio frequency has been investigated over broad frequency ranges, including in a paper from our 9-year data set, this is the first study that investigate the functional form of the frequency dependence. We detected jitter in 43 of the 48 pulsars analyzed, with 30 of them showing significant frequency dependence.